I love science. One of my earliest childhood memories is of my dad getting out basketballs and tennis balls to mimic planetary orbits with me. In high school, my Physics teacher brought science to life; Mr. Bergeon received regular awards and became one of the most respected teachers in my state. [1] People like my dad and Mr. Bergeon fueled my appreciation for science and inspired me to study Engineering in college.

I am certain that science can help us understand and engage the world better. But does science have the explanatory power to tell us what is ultimately true or provide meaning to our existence? Even the most ardent atheist scientists appear to think not . . .

Putting Science and Faith at Odds

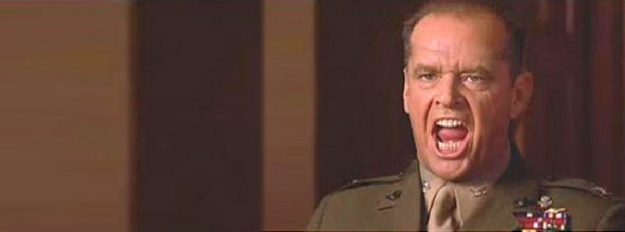

One such scientist is Jerry Coyne, author of Faith Versus Fact: Why Science and Religion Are Incompatible. The premise of the book is pretty straightforward: science deals with facts and religion can only operate on superstitions. Religion is a hindrance to humanity and we would all be better off without it. Throughout the book, Coyne offers relevant insights that Christians and people of other faiths ought to take into consideration. But I want to focus on an essential takeaway from Faith Versus Fact. Science, as understood by Coyne and those in his camp, “can’t handle the truth.” Coyne all but admits this from the outset:

“In this book I will avoid the murky waters of epistemology by simply using the words “truth” and “fact” interchangeably. These notions blend into the concept of “knowledge,” defined as “the apprehension of fact or truth with the mind . . . Scientific truth is never absolute, but provisional” (29-30).

Truth-Dodging

Epistemology is one of those big academic words which basically means the study of how we know what we know—in other words, how we rightly say that something is knowledge. Coyne’s quote above may sound sensible on its surface, but it places severe limits on what we can ultimately know, and it prescribes very restrictive means for how we might get there.

First, notice that by evading discussion of epistemology, he is altogether sidestepping the main issue. None of us simply wants to be told what is true; we want to how we can know truth. Furthermore, we want to know we’re working off the same definition of truth. That’s what the whole discipline of epistemology is about. Coyne essentially says, “I don’t want to debate the ways humans might identify truth or gain knowledge; just take my word for it—science is the only option.”

Second, to equate truth with scientific facts will not do. Science is valuable but far from flawless. Why should we assume data and explanations surfaced by fallible scientific communities are the only valid sources of truth? [2] That won’t satisfy most of the planet, which is one reason humanity continues to pursue multiple paths of discovering truth. Coyne’s chief rebuttal is that the other paths, like philosophy and religion, don’t satisfy him. [3]

Coyne’s Science Can’t Handle the Truth

Next, notice that truth is impossible to ascertain under Coyne’s paradigm. Even if scientists could never do wrong, truth would still be “provisional”; it can never be known with confidence. Whatever apparent “facts” we might have are merely the best we can do for now. That sounds humble and attractive on the surface, but Coyne fails to explore the gravity of his position—it means we can never really be confident that we know anything. Truth is always up for grabs. But that’s not the way humanity has defined truth throughout history. Truth is what corresponds to reality, regardless of whether our minds have comprehended it. Our understanding of facts may be provisional, but truth itself does not change. According to Coyne, “scientific truth” can change, so we’re never left with anything that sticks.

Here’s why Coyne’s subtle evasion of the epistemology/truth discussion is so significant: the search for universal, unchanging truth is the whole venture. It’s what we care about, what most of the world desperately wants to discover. In the end, Coyne says science can’t provide unchanging truth, but we are all fools for seeking additional means to get to it. That’s not a scientific attitude. Not only does it discourage open-minded discovery, it borders on cruelty toward a human race that longs for answers.

Science, Origins, and Our Deepest Questions

Beyond its limitations concerning truth, the science promoted by Coyne also lacks the power to explain the ultimate origins of reality. I was surprised by his admission to this and I wonder if he realized its implications for the entire proposal of Faith Versus Fact:

“There are also difficult problems that science hasn’t yet explained—the origin of life and the biological basis of consciousness are two . . . given their difficulty, some may never be solved” (153).

The problems that Coyne says science may never solve are the very issues other disciplines like theology and philosophy directly explore. Once again, we’re left bewildered—why would those who believe science may never answer these questions jettison other potential means of addressing them? That’s not a scientific posture, it’s not logical, and it’s certainly not compassionate.

The next article, will take up another area that presents problems for scientists of Coyne’s persuasion: Can Science Give Us Meaning and Morality?

_____________________________________

[1] I believe Mike Bergeon is now retired but he maintains a high ranking on Rate My Teachers: https://www.ratemyteachers.com/michigan/teachers/52

[2] Coyne rightly argues that religious and philosophical groups often disparage science as wholly untrustworthy and subject to bias. However, the fact remains that the scientific enterprise is and always will be a fallible human pursuit. No matter what scientists’ intentions, it is subject to errors, collective bias, groupthink, and sometimes fraud that may or may not be detected. Also, students of history will recognize Coyne’s assessment of religion in Faith Versus Fact as sorely misinformed—Christians have generally supported and propelled courageous, ethical scientific discovery throughout history. Certainly, there are cases to the contrary.

[3] Coyne offers other reasons for his conclusions, most notably that religious means to truth acquisition have never produced widespread agreement about which belief system is right. But lack of consensus does not prove that consensus will never arrive, nor that any given religious explanation might not already be true.