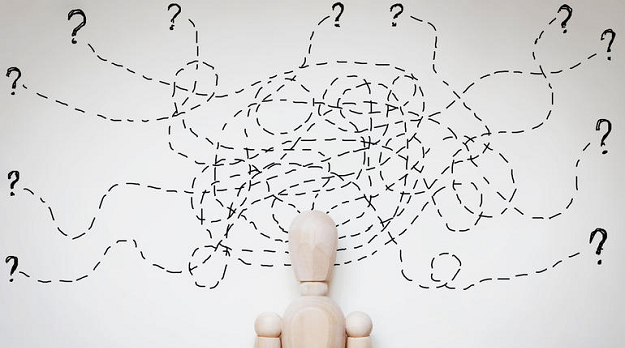

The last Discernology post called into question the modern trend in preaching to emphasize one main point or proposition in a sermon (commonly called the “Big Idea”). [1] We challenged the notion that this is appropriate for every sermon. Even if a passage of Scripture intends to communicate a primary point, constructing a message solely around one main idea without surfacing other colors and nuances of the text may leave the hearers substantially undernourished.

Bible practitioners and scholars alike have long treated the parables of Jesus as stories which culminate in a central claim or principle. For the most part, they are right. Ironically, that is precisely why the parables make excellent candidates for challenging the Big Idea approach to preaching.

Parable of the Prodigal Son

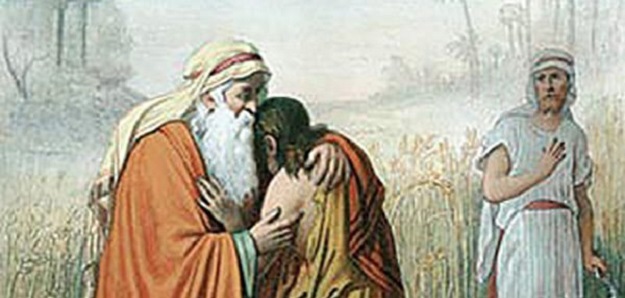

Consider one of Jesus’ most famous parables found in Luke 15:11-32: The Parable of the Prodigal Son. Jesus has been teaching his disciples in the Gospel of Luke using striking imagery—imagery which also serves to chastise the Pharisees for mismanaging their role as spiritual leaders of the Jewish people. It is critical not to overlook what Jesus is doing here – he is indirectly confronting the Pharisees (represented by the older brother) for their attitude toward lost sinners and their own undetected spiritual estrangement from God the Father.

Historically, a lot of preachers have missed the Pharisee-centered aspect of the parable, choosing instead to highlight the prodigal son’s sin, repentance, and return to his benevolent father. It isn’t hard to see why: in most cases, people can relate more naturally with the prodigal son than with the older brother. But preachers eventually realized that the older brother was often ignored, so today’s trend is to criticize preachers who don’t center their sermons around Jesus’ apparent main target—the religious leaders.

Surely preachers should address the older brother and relate him to their hearers. For this particular parable, I would say that a sermon should culminate in a challenge to “religious people” who may not see their own spiritual poverty and wrong attitudes toward others who have not been redeemed by Christ. But here is a key question: How can we retain emphasis on the older brother while doing justice to the intricate, powerful elements of the parable in its context?

Exposing the Colors in Luke’s Gospel

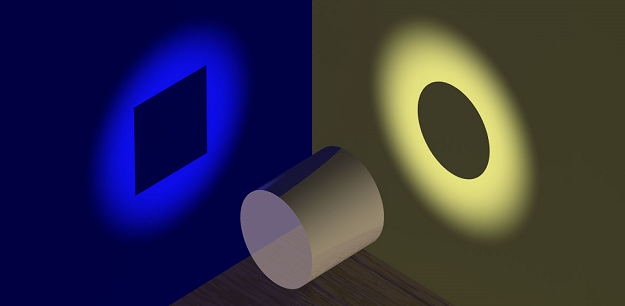

To put the question another way, how do we expose all of the colors present in the kaleidoscope which is the Parable of the Prodigal Son? The first step is to consider all that Luke has written to this point in his gospel. For example, more than any other gospel writer, Luke has emphasized God’s love and outreach to the downtrodden and to sinners without God in their life. If you were reading Luke 15 for the first time, you would undoubtedly think about the previous 14 chapters which show the constant compassion of Jesus through healing, acts of generosity, exorcisms, and forgiveness. The immediate context, Luke 15:1-10, reveals God’s compassion for lost sinners and his joy when they repent.

So even if Jesus’ primary intention in the Parable of the Prodigal Son is to highlight the Pharisees’ misguided attitudes, our appreciation for Jesus’ teaching arises from all the other truths that have brought us to this point in the text.

Colors of the Prodigal Parable

The Parable itself vividly expands on these prior truths in Luke. As such, it is hard to imagine covering Luke 15:11-32 without highlighting the profoundly moving elements of the narrative and challenging hearers to take a deep look at themselves in light of realities such as the following:

- The prodigal son’s hurtful rejection of a Father who provided everything for him. He even had the nerve to ask for his father’s blessing to sever their relationship. (How could any of us reject such a good God?)

- The attractive but abusive force of this world upon those separated from the Father. (How could this fallen world not enslave? Why would we possibly think we could escape its harm?)

- The prodigal’s conviction that he could still humbly return to his Father and believe he would be accepted. (Do you believe God would accept you, no matter how severely you’ve rejected God?)

- The instinctive, explosive celebration of the Father at the prodigal’s return. (Do we really believe we have a Father who is that good? Does he love us and other lost sinners that much?).

The above elements alone ought to move any hearer before they come to the older son’s shocking, inexplicable, indignant response to his brother’s return (15:29-30). Given all that Luke has written to this point, it is unthinkable that the second son would have such a stubborn and unforgiving attitude. Did you notice that the parable is open-ended? We don’t know whether the older son is going to accept his Father’s instruction, recognize the Father’s goodness, love his younger brother, and repent of his hardheartedness. (Will we?)

The four points above highlight some of the critical “colors” of the whole passage. The Big Idea of the Parable of the Prodigal Son would be a dud if Jesus had not told the whole story and included this rich picture of who God is—and who we are. In order to repent, both the older and younger sons must recognize sin’s scheming, seductive nature and be won over by the Father’s extreme love. So even if the Big Idea revolves around the older son, the powerful “mini-sermons” within the passage leading up to the Big Idea are just as vital and they are what turn hearts to God in the end.

“Retweeting” Kuruvilla

I thought I’d wrap up this article with some of the most stimulating quotes found in Kuruvilla’s “Time to Kill the Big Idea”:

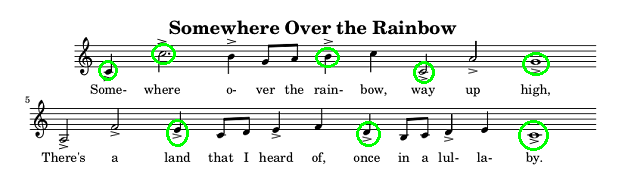

“To convert the text into a Big Idea is surely going to entail significant loss of its details, meaning, power, and pathos, thereby deflating the thrust/force of that text . . . equivalent to a photo of a person, or the theme of a musical work, or the summary score of a ball game that can never substitute for the real thing.” (832)

“A story is a way to say something that can’t be said any other way, and it takes every word to say what its meaning is. You tell a story because a statement would be inadequate.” (836, quoting Flannery O’Conner)

“A contemporary preacher ‘seems like a second-rate lawyer arguing a case.” (837)

“The preacher is the curator . . . preachers are to let their listeners encounter and experience the text as they themselves did when they were studying.” (842)

“The preacher is to be co-explorer of the text with the flock, not chief explainer of the text to the flock.” (843)

“The doing of the authors ought to be the interpretive goal of preachers—the discernment of the text’s thrust/force . . . without which there can be no application.” (838)

____________________________________

[1] The article was inspired by Abraham Kuruvilla, “Time to Kill the Big Idea? A Fresh Look at Preaching,” JETS 61, no. 4 (2019): 825-46.